The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) is a regional pact among 54 of the 55 African Union nations that establishes a single market and reduces trade frictions for the movement of goods, services, capital, and people within the continent.

- Context: The reported share of intra-African trade has historically been low, averaging 13% for intra-imports and 20% for intra-exports over the last seven years, though the reality is likely much higher due to informal trade and skewed totals reflecting activity in a few export-oriented heavyweights like Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, and Angola.

- What does the new agreement do? Since its launch in January 2021, the AfCFTA has created the largest free trade area in the world by number of ratifying countries, connecting 1.3 billion people from participating economies with a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion. The deal removes 90% of tariffs, simplifies customs procedures, standardizes fiscal terms, and addresses frictions with labor, taxation, and intellectual property management. The Protocol on Trade in Goods provides non-discrimination in tariff treatment, meaning concessions, privileges, or immunities granted to one nation extend to all other member countries, and encourages mutual removal of import and export duties, quantitative restrictions, and rules of origin for cross-border trade. The Pan-African Payment and Settlement Platform (PAPSS) cuts hard currency conversion from inter-bank transfer, enabling instant local currency transactions between merchants in ratifying countries.

- What are the expected macro-level impacts? The deal allows participating countries to create a trade buffer amidst increasing global trade protectionism, including in clean energy, and bargain collectively on the international stage. Estimates vary, but the collectively ratified terms of the AfCFTA by 2030 could increase:

- Combined consumer and business spending on the continent to $6.7 trillion annually.

- Real income gains by 7%, or nearly US $450 billion.

- Total export volume by 29% relative to business-as-usual growth (Intercontinental exports would increase by 81% and exports to non-AfCFTA markets by 19%).

- Intra-African trade value by 15 – 25% by 2040, equivalent to between $50 – 70 billion in nominal dollars.

Here’s how AfCFTA could de-risk the power sector

- Increased industrial production means increased industrial electricity demand. The African continent’s exports have averaged about 75% unprocessed primary commodities and solid minerals since 2007, and 40% of intra-African exports are manufacturing commodities. Currently around 70% of value addition for African commodity exports occurs outside the continent. Increased intra-African trade would boost domestic manufacturing demand and demand for productive power as a result.

- Dispute resolution mechanisms and harmonized regulations will drive down private equity risk premiums and diligence for new power infrastructure projects financed by foreign capital. This includes IPP developments, transmission and distribution infrastructure, and even gas-to-power networks, where appropriate. Power infrastructure projects can be scaled up to serve regional, rather than only national needs. This is especially relevant for cross-border projects, where before the AfCFTA, the fear of outsized influence of heavyweight market participants could hamper regional integration.

- Nondiscriminatory tariff-setting and simplified customs procedures help to facilitate cross-border transactions for electricity and fuels. Electricity is a tradable commodity, but cross-border exports are only about 3% of global power production, compared to roughly one-third of global gas production and two-thirds of global oil production. The terms of the AfCFTA can promote harmonization of electricity remuneration frameworks, wheeling schemes, and efficient development of bilateral power trading contracts between countries. AfCFTA markets that will soon find themselves with excess generation capacity (such as Egypt, Kenya, Senegal, Ethiopia, and possibly the DRC) can become key regional power suppliers to their power deficient neighbors.

- AfCFTA-led cooperation could improve on the gaps and inconsistencies in the continent’s five regional power pools. Africa’s five power pools can provide savings and improve bankability to utility-scale generation projects, but have been hampered by underinvestment in transmission and distribution, inconsistent regulatory and tariff regimes, and breakdowns in regional cooperation. Reduced trade barriers and increased cooperation from AfCFTA could improve regional power pooling by aligning local regulations with regional initiatives and increasing transparency and trust between utilities. It could also open the door to cross-border wheeling schemes between corporate entities, and allow IPP developers and investors to access more and varied sources and shapes of power demand and sidestep some of the drawbacks of market fragmentation.

- Increased regional cooperation improves energy security for all. Security of supply is reinforced by the ability to source operating reserve capacity from a neighboring market’s power sector.

Significant structural barriers remain

Overlapping existing regional economic integration arrangements, such as the Southern African Customs Union and the East African Community (EAC), can complicate the negotiation and interpretation of bilateral AfCFTA negotiations, particularly regarding most-favored-nation (MFN) tariffs, intellectual property, and competition. Until AfCFTA terms are clarified and develop precedents in implementation, foreign investors may need to look to existing agreements for investment protections not offered under the AfCFTA. Additionally, while a unified market structure will be positive for infrastructure investment, manufacturing, and power demand, growth is predicated on adequate roads, bridges, ports, power lines, and other forms of enabling physical infrastructure, not to mention legal and digital infrastructure.

Benefits will accrue over time, and increasingly unified market power will help cooperating countries with burgeoning middle classes throw their collective weight around in the global supply chain. The AfCFTA removes major barriers to intra-African specialization and gains from trade, key to economic growth and the high-energy future African countries will need to power it.

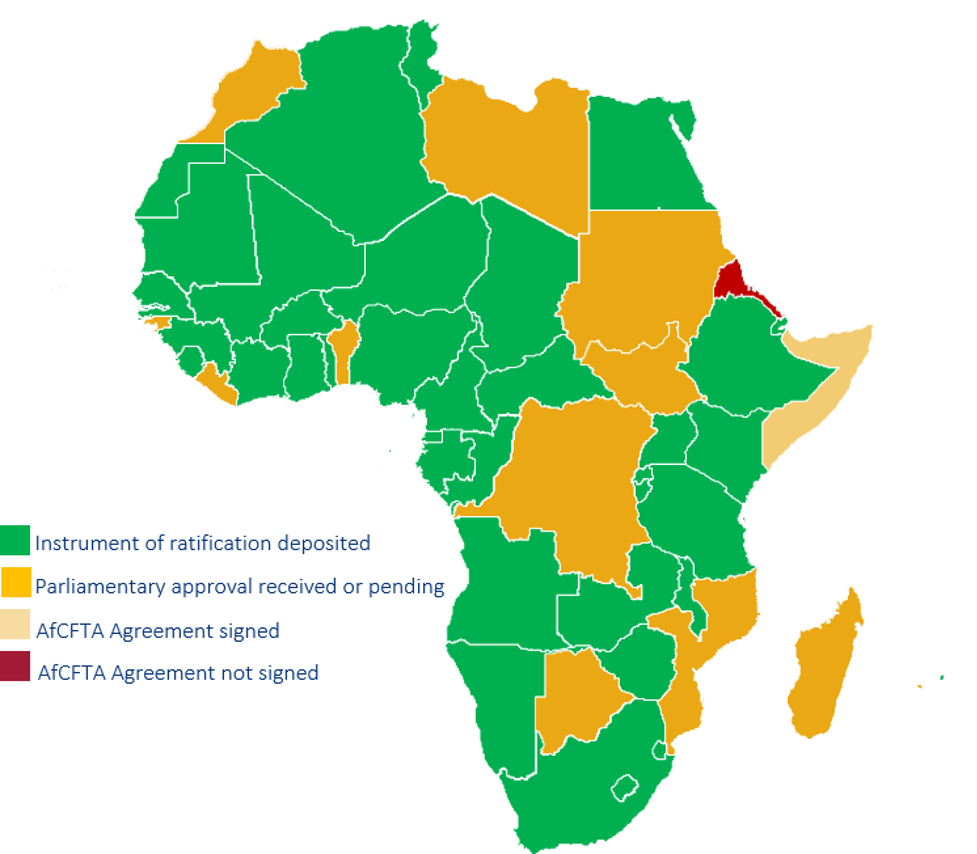

FIGURE 1: AfCFTA member states

Data source: Tralac.org