Mozambique, one of the world’s poorest countries with a GDP per capita under $500, is also home to Africa’s third largest confirmed reserves of natural gas. Estimated around 125Tcf in the Rovuma Basin alone, Mozambique’s natural wealth has attracted the attention of oil supermajors Eni, ExxonMobil, and Total SE. The scale of the resource dwarfs the country’s existing economy. Current annual GDP in Mozambique is ~$15 billion, while projects to extract and export LNG in the country could reach $50 billion in foreign investments. The government expects to earn $95 billion in gas revenues over the next 25 years.

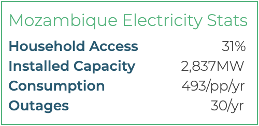

Mozambique is heading toward a future as a top-10 global LNG exporter, but if it reaches that goal it will be the only country on the list without universal electrification. While it currently exports power to neighbors including South Africa and Zimbabwe, only 31% of Mozambicans have access to electricity and its per capita power consumption is low. Mozambique’s power system also scores poorly on reliability metrics, whether via enterprise surveys (used in the Hub’s RACE) or SAIDI/SAIFI indices.

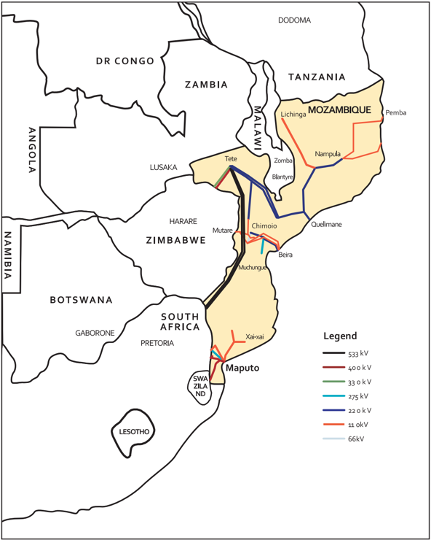

Mozambique’s generation capacity is currently dominated by the 1970s-era Cahora Bassa dam, which provides the bulk of the country’s current power. Nearly 80% of the country’s power mix is hydro, with the remainder mainly gas, while some solar is planned. While Cahora Bassa provides over 2GW of installed capacity, over 80% of its production is exported to South Africa. This export-oriented model is apparent in a map of their grid (Figure 1), which shows a high-voltage export line power from the northwest to South Africa, while power for southern Mozambique is imported from South Africa. The domestic grid remains sparse and regionally fragmented.

Mozambique’s natural gas resources provide a potentially transformational opportunity to address the country’s energy poverty and power inclusive economic growth. But it won’t be easy – or automatic. Traditional challenges include weak governance and limited existing power infrastructure, which aren’t quick or easy fixes. More critically, recent violence by Islamic State-linked insurgents is escalating and threatening to spill over into Tanzania. Private security companies operating in the gas-rich regions have also been accused of terrorizing the local populace.

FIGURE 1: Export-oriented transmission system in Mozambique

Source: “Renewables Readiness Assessment: Mozambique” IRENA

So what might Mozambique do?

- Follow through on commitments to ensure transparent use of gas revenues. In early 2019, the government announced its intention to establish a sovereign wealth fund to direct gas revenues to fund infrastructure, poverty alleviation, and economic diversification. The promise of this approach depends on a high degree of transparency.

- Devote significant gas revenues to energy infrastructure. Directing a major share of expected revenues to reinforcing and building out the power grid, investing in domestic generation, and strengthening the national utility would have huge positive impacts that would spill over into other productive sectors.

- Set reasonable expectations among the domestic population for local gas use. Mozambique is an energy-rich low-income country, so there is already considerable domestic political pressure to use substantial gas at home, rather than export it all. Some can be used for local generation, industry, or cooking. But even if Mozambique were able to double its electricity consumption annually and used only gas without any contribution from hydropower or solar, it could still only use less than a fifth of Total’s expected exports.

- Deepen integration within the regional power pool. Mozambique already has major infrastructure for regional electricity trade, and is building more to Zambia and Malawi. Home to the largest power generation potential in the region, Mozambique could further leverage its newfound gas by expanding electricity exports within the South African Power Pool. This would both diversify revenue growth and help to stabilize the regional power system but would require significant new generation capacity in-country.

What can the international community do?

- Invest in infrastructure for domestic energy consumption. The $15 billion investment raised by EU-based Total for its Mozambique LNG project will be the largest private investment in Africa ever, but will be primarily to export the gas to wealthier countries in Europe and Asia. Development financiers should be making parallel investments in generation facilities to use some of that gas domestically, and in the transmission and distribution needed to get power to Mozambican homes and businesses. Institutions like the US Development Finance Corporation are showing what a balanced approach looks like.

Mozambique is on the cusp of a unique opportunity for transformative change and industrialization. Vast gas resources can be leveraged directly to provide power generation for expanded access and economic activity, and indirectly as a major revenue source to fund infrastructure for long-term national development. Success will depend on a high degree of transparency, and on both Mozambique’s government and international partners prioritizing domestic benefits.