The Caribbean islands rally firmly behind the “1.5° to stay alive” movement, for a limit to 1.5°C of global warming over pre-industrial levels before the end of the current century.1 At the current pace, the earth has already seen 1.1°C of warming.

Many Caribbean islands are already experiencing annual hurricane damages that exceed 0.5% of GDP on average, which will only intensify without drastic global climate action.2 As such the Caribbean is prioritizing adaptation to shore up critical infrastructure that may reduce the costs of climate-related disasters and build resilience to future shocks. Despite ambitious climate targets and a regionally adopted Caribbean Sustainable Energy Roadmap and Strategy, access to international financing for resilience remains challenging.

Challenges of access to finance for resilience

Climate funders (such as the Green Climate Fund, the Global Environment Facility, the Adaptation Fund, and Climate Investment Funds) follow complex processes for grant applications, require an exceptionally high standard of project design, and often require that the entities applying for grants be accredited, which can be a difficult undertaking.3

Aside from the sheer complexity of accessing funds, the Caribbean region faces many challenges in securing the scale and type of finance to invest in infrastructure for resilience.

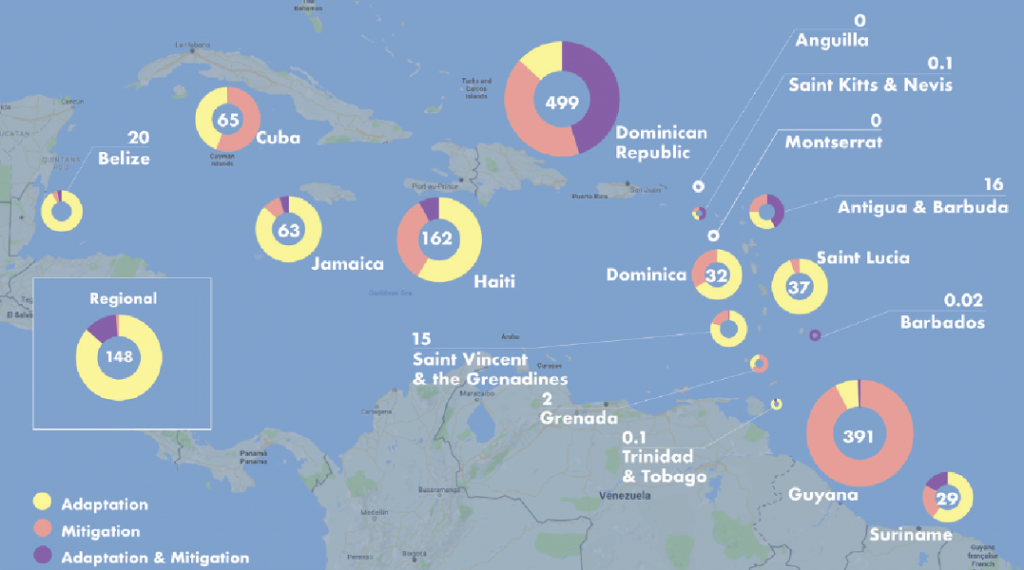

- Climate finance only accounted for 6% of the region’s total reported aid flows from 2010 – 2015.4

- More than 50% of these funds were designated for mitigation activities, and

- More than half of the total was two bilateral mitigation-specific grants to Guyana and the Dominican Republic, from Norway and France respectively, heavily distorting the picture of available finance across the region.4

Further, “general environment protection” received the most climate finance, while some sectors critical for long-term resilience, such as health and education, have not received any climate finance. Finally, the amounts described above are committed amounts, rather than actual expenditure. Disbursement ratios vary across countries, and in some cases are very low. Across the region, climate finance disbursements in 2010–2015 equalled only about 39% of total commitments.4

FIGURE 1: Summary of climate finance in the Caribbean, 2010–2015 (committed amounts in million US$)

Source: SEI

These challenges in securing finance for resilience stem from three main characteristics of Caribbean islands:

- Limited access to international capital markets: Caribbean access to international capital markets is costlier and more constrained due to its small markets and limited opportunity for returns— the increasing importance of private climate finance thus poses a key challenge.5

- Ineligibility for overseas development assistance (ODA): Meanwhile, accessing concessional finance, grants, and non-reimbursable funds is equally difficult, as most islands are considered middle or middle-high income by GDP per capita metrics, poorly reflecting the real distribution of wealth. ODA to the region has been on a clear downward trend relative to other developing regions recently.6

- High debt compounded by the pandemic and increasing hurricane intensity: Structural characteristics, including limited economies of scale, global trade policies insensitive to small export capacities, and an over-reliance on imported goods and seasonal industries such as tourism, contribute to the Caribbean islands being among the most indebted countries in the world.7 Servicing debt requires ongoing payments, on average over 20% of total government revenues.8 This reduces the national budgets available for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction, thereby increasing vulnerability.

These characteristics place the region in a high-risk category that makes borrowing difficult and unsustainable, and the high interest rates applied to loan-based financial instruments for disaster recovery only further exacerbate existing debt.

Resilience finance opportunities are emerging

Resilience-focused funds and investment coalitions are emerging to address this need:

- The Caribbean Climate-Smart Accelerator is a public-private initiative of the 2017 One Earth Summit by 26 countries and more than 40 private and public sector partners to invest over $8 billion and make the Caribbean the world’s first “climate-smart” zone.9,10 Its Caribbean Blended Finance for Resilience Fund will source equity, impact investment, mezzanine capital, debt and a risk mitigation window, with a focus on sustainable energy.11

- The Inter-American Development Bank also launched its Sustainable Islands Platform in 2017, committing to US$1 billion in loans and grants over five years and the support of a growing blue bonds market. These funds have been disbursed through programs such as the Pilot Programme for Climate Resilience in Jamaica, which made a total of US$ 7.2 million available to small enterprises in tourism and agriculture over the past five years to finance resilience initiatives island-wide.12

- The Caribbean Regional Resilience Building Facility established between the European Union, the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction & Recovery, and the World Bank, set up after 2017 hurricanes Irma and Maria provides technical assistance, expanded risk insurance coverage, and adaptation grants to either directly co-finance resilience investments or ancillary needs.13

- Other new or existing global initiatives include the global private sector‐led Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment (CCRI), and the Adaptation Finance Mainstreaming Program which supports standardization of macro, fiscal, budget, and procurement policies.14

More is needed: strategies to expand access to finance

These global commitments to support resilience-building in the Caribbean are important signals, but the region needs much more support, starting with five key strategies for increasing access to finance:

- A comprehensive regional resilient investment plan based on data and credible projections to inform decisions on financing and loss & damage support needs.

- More direct cooperation between the international community and the public and private sectors to harmonize cost-benefit analysis methods that emphasize social and environmental criteria, which would bring resilience projects more into the purview of private markets.

- Allowances for small island countries that have graduated out of ODA to be able to access financing, especially concessional quality finance which can take the risk necessary to support disaster preparedness activities.

- Exploring innovations such as “debt for climate swaps” in which creditors forgive debt in exchange for a commitment by the debtor to use outstanding debt service payments for national climate action programs.15 The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) is calling for a SIDS compact to provide debt relief and fiscal maneuvering space for islands.

- Addressing the compensation of loss & damage with high priority because there are real limits to adaptation.16 Liquidity in the face of disaster is already scarce. Natural disaster clauses should be included in new and existing loan agreements that provide liquidity in crisis without pushing loans into default. Likewise, AOSIS leaders are calling for the development of a global disaster mechanism to provide crucial liquidity in the event of climate disasters.

The Caribbean position for COP 26

While the global target to mobilize US$ 100 billion per year by 2020 for adaptation and resilience in vulnerable countries is an important ambition, far more finance is necessary.17 Wealthy countries must respond by ensuring that highly vulnerable small-island regions have access to sufficient finance to shore up their defenses against climate change.

Endnotes

- Sealey-Huggins, “‘1.5°C to stay alive’: climate change, imperialism and justice for the Caribbean,” Third World Quarterly, 2017.

- World Bank, 2021.

- CDKN, 2020.

- “Climate finance in the Caribbean,” SEI, 2017.

- “Resilience and capital flows in the Caribbean,” Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2018.

- “Financing for development challenges in Caribbean SIDS,” UNDP, 2015.

- “Why have Caribbean countries been so indebted, and what can they do to improve outcomes?” IDB, 2021.

- “Financing for development challenges in Caribbean SIDS,” UNDP, 2015.

- Caribbean Climate Smart Accelerator.

- IISD, 2018.

- Caribbean Climate Smart Accelerator.

- Jamaica Information Service.

- Caribbean Regional Resilience Building Facility.

- Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment.

- Thomas and Theokritoff, “Debt for climate swaps for small islands,” Nature Climate Change, 2021.

- Thomas et al., “Global evidence of constraints and limits to human adaptation,” Regional Environmental Change, 2021.

- “Regional dialogues call for scaled up finance for hard-hit Caribbean region,” Relief Web, 2021.